posted by Lexing Xie and Alex Mathews

What’s the background on this research?

Alex Mathews has been on a quest to connect vision and language since the beginning of his PhD. The overarching theme of his dissertation is on describing pictures in interesting and human-like ways. Having more interesting and engaging captions will affect many interactions and decisions in our social lives, from daily picture sharing, to deciding a dinner venue, to whom to vote for in an election.

This research was prompted by the nice results from our previous SentiCap paper that writes sentimental image captions – especially after colleagues called out to us for liking the memorable examples of the white fluffy dog on a computer and the dead man on skateboard – but two more ambitious goals were calling out to us.

The first is being able to compose captions in any linguistic style – these styles can be defined by an author (e.g. Shakespeare), a source (e.g. NYTimes), or a collection of existing texts (e.g romance or detective novels). The second is being able to learn like humans do – read some text in the target style, and start mimicking what it reads like. This second goal is new and challenging for image captioning systems, since SentiCap and its related systems, such as Show-and-Tell and StyleNet, require aligned training data (e.g. one image paired with sentences that describe it, possibly in different styles). This kind of training data is hard to curate due to two reasons. Firstly, collecting the corresponding styled sentence for a given image and its descriptive caption is time- and resource-consuming. In SentiCap it took us three design iterations and more than $1,000 to curate about 3,000 training sentences that contain the sentiment. Secondly, it is difficult to tell writers what to write and perform quality control that crowd workers write, once we’ve moved beyond positive and negative sentiments. For example, how can one tell 1,000 crowd workers to write something “Shakespeare-ish” that describes the pictures above?

What was the methodology you used?

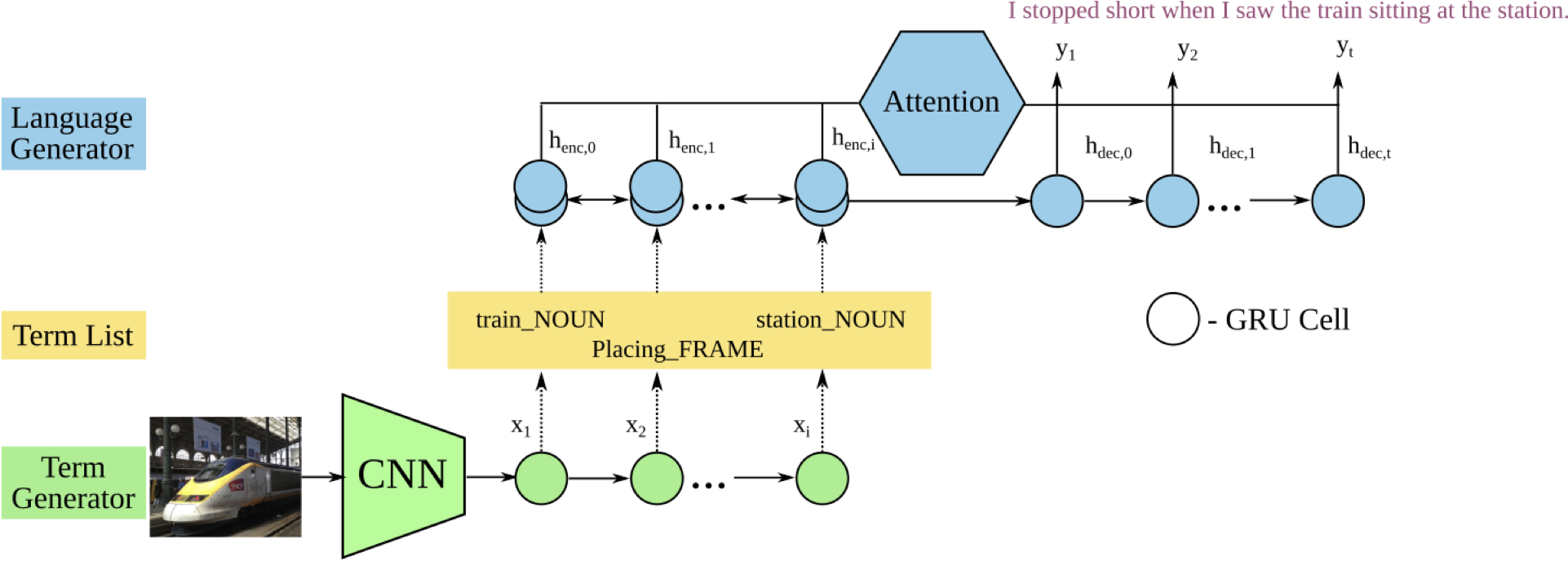

After more than a year of searching and trying different designs, we finally settled on two machine learning components that specialise in their respective tasks. The first component distills an image into a small set of content words (such as train, sit, platform), and the second component articulates a sentence in the given style from a set of content words (such as I stopped short when I saw the train sitting at the station). These two components are variants of recurrent neural networks that represent the state-of-the-art in natural language tasks such as machine translation. Furthermore, there is an attention component that explicitly connects the content words to some of the output words, to ensure that they are covered in the output.

To learn this two-part model, we require two separate training corpora. The first one is from images to content words – this is available in widely used image caption datasets such as MSCOCO. One crucial design choice is what makes the content words – in this work they are the nouns and verbs from the training captions. In particular, words are normalised into their lemmas (so that boxes become box), and verbs are generalised to a broader class of verbs that has similar meanings in what is called FrameNet hierarchy – this makes sitting and standing both verbs of a placing action, and gives the model more flexibility in which one to use when describing a train. The second corpus is a large collection of romance novels, roughly half a million sentences with related visual concepts. These story-like sentences are stripped into their respective content words, and then a language model learns to generate the original sentence from these words.

What was the main finding of the research?

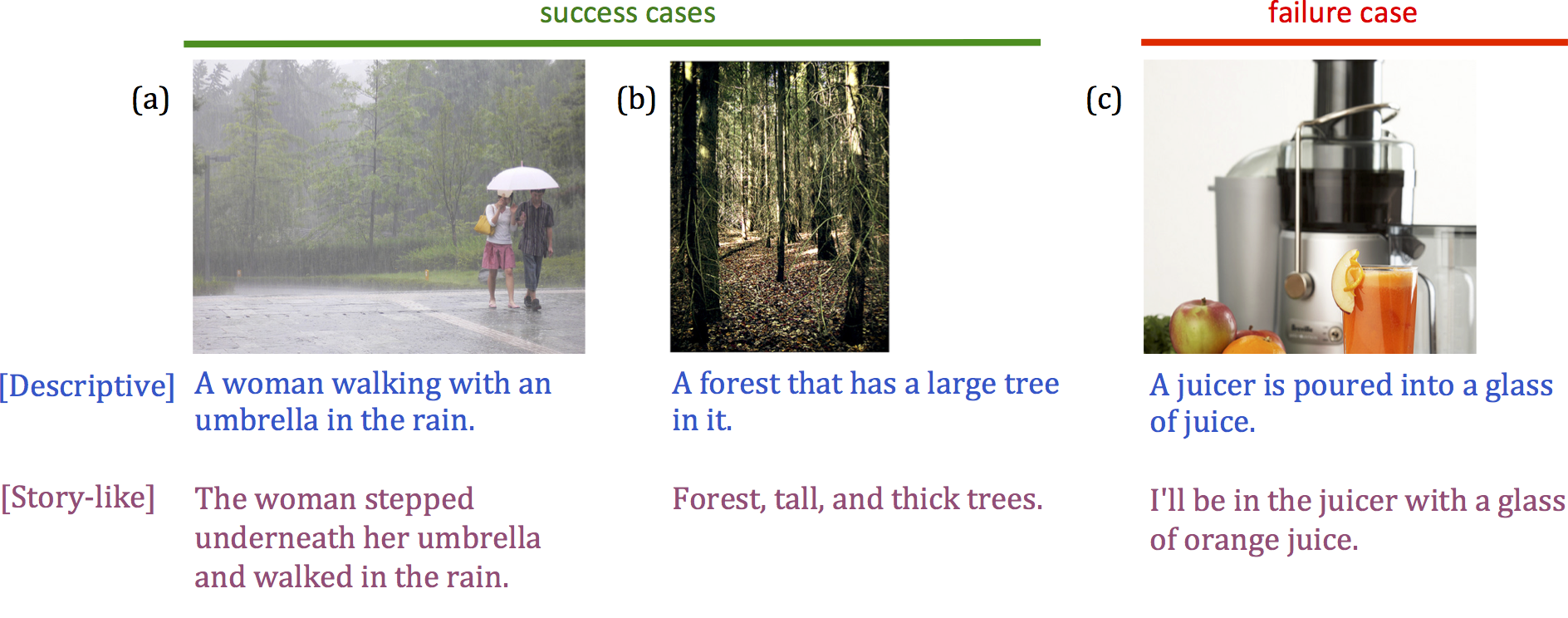

It is encouraging that one can separately distill content and articulate style with current machine learning approaches. We are pleased to see that the model has learned to pick more versatile words for expressing the same meaning. The breakthrough for human-like style generation comes from connecting the semantic gist of a sentence (i.e. the content words) to a powerful language generator that learns the word sequence patterns in the given style.

Did anything surprise you in the research?

Being romantic goes beyond one sentence! Initially we planned to write romantic captions, but it soon dawned on us (upon seeing the first batch of results) that being romantic relates not just to how each sentence is said, but more to the storyline and theme of the entire novel. The outcome from our system was legitimately story-like, but a dozen or so words in a sentence was not sufficient to justify it being romantic. What the language model did learn, however, was to use more past tense, definite articles, and adopting a first person view in the narrative, all of which are typical of story-telling in novels.

What does this research tell us about the language abilities of AI?

Machine has gotten a lot better in analyzing and generating natural language. We share the excitement that they could be a lot of help to people for their daily tasks. We would think that machine-learning would help the literarily challenged to compose succinct and stylish messages, or even write engaging press-releases for our research (replacing me as a writer)!

Many open questions remain in this area, with room for many theses by aspiring PhD students and young researchers. One such challenge is to endow the machine to be informed by commonsense and encyclopedic knowledge of the world when it writes. A related challenge is for machines to compose beyond a sentence – writing coherent paragraphs and holding intellectually charged conversations.

What’s next?

Alex recently submitted his PhD thesis and is moving on to the next stage of his career! The lab will continue the quest to make connections among images, language and knowledge on the social web.

Resources

Alexander Mathews, Lexing Xie, Xuming He. SemStyle: Learning to Generate Stylised Image Captions Using Unaligned Text, in Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR ‘18), Salt Lake City, USA, 2018.

| Download: | Abstract | Paper+supplement PDF |

|---|---|

| code & models (upcoming) | Github repository |

| Bibtex: |

@inproceedings{mathews2018semstyle,

title={{SemStyle}: Learning to Generate Stylised Image Captions using Unaligned Text},

author={Mathews, Alexander and Xie, Lexing and He, Xuming},

booktitle={Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR)},

year={2018}

}