Posted by Lexing Xie. Thanks to Mario Günther, Ignacio Ojea Quintana, Swapnil Mishra and Atoosa Kasirzadeh for many great suggestions.

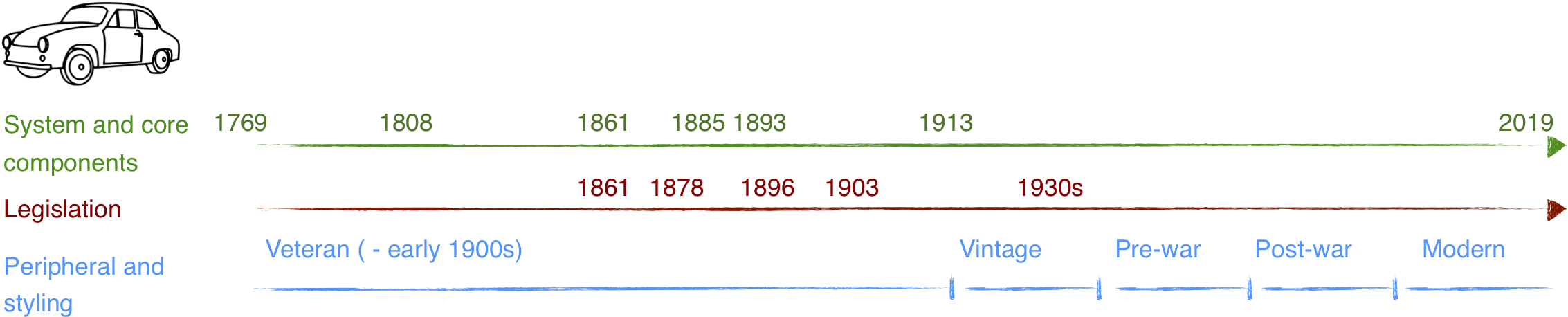

Fig. 1: Overview of three concurrently evolving timelines in the development of cars2. Top (green) - key events in engine and early system developments. Middle (red) - key events in car and road-safety related legislations. Bottom (blue) - rough separation of eras in car styling. Key events selected from Wikipedia narratives on cars and history of the automobile3. See article for discussion. For readability, time scales are not uniform.

In the past few years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) entered everyday conversations as both the boon and bane for our futures.

In this article, we draw a seemingly remote analogy between AI and cars.

While separated by the software/hardware boundary, AI and cars are complex machinery that have been under rapid development for half a century or more, and are now (or will be) an integral part of our daily lives.

We review the development of cars since the 18th century as three concurrently evolving timelines including the core technology, the legislation (and the needs driving it), and peripheral components, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The goal of the historical narrative is to highlight several similarities in the history of cars and recent developments in AI, including the excitement of how new technology shapes our world and the fear of its danger and negative effects.

The Chinese saying has it that one can use history as a mirror4, we hope this analogy will help the community reflect the path for AI and shape what may happen.

This post pays tribute to the recently launched ANU Humanising Machine Intelligence (HMI) project.

The idea for writing it originated from a talk I gave at the invitation of HMI colleagues1.

We also invite the readers to envision the goals and approaches to humanising Machine Intelligence (MI) through a familiar machine.

1. Core components and systems

An automobile is a complex driving machine with tens of thousands of moving parts7.

We start the discussion on cars from its core power source – the engine.

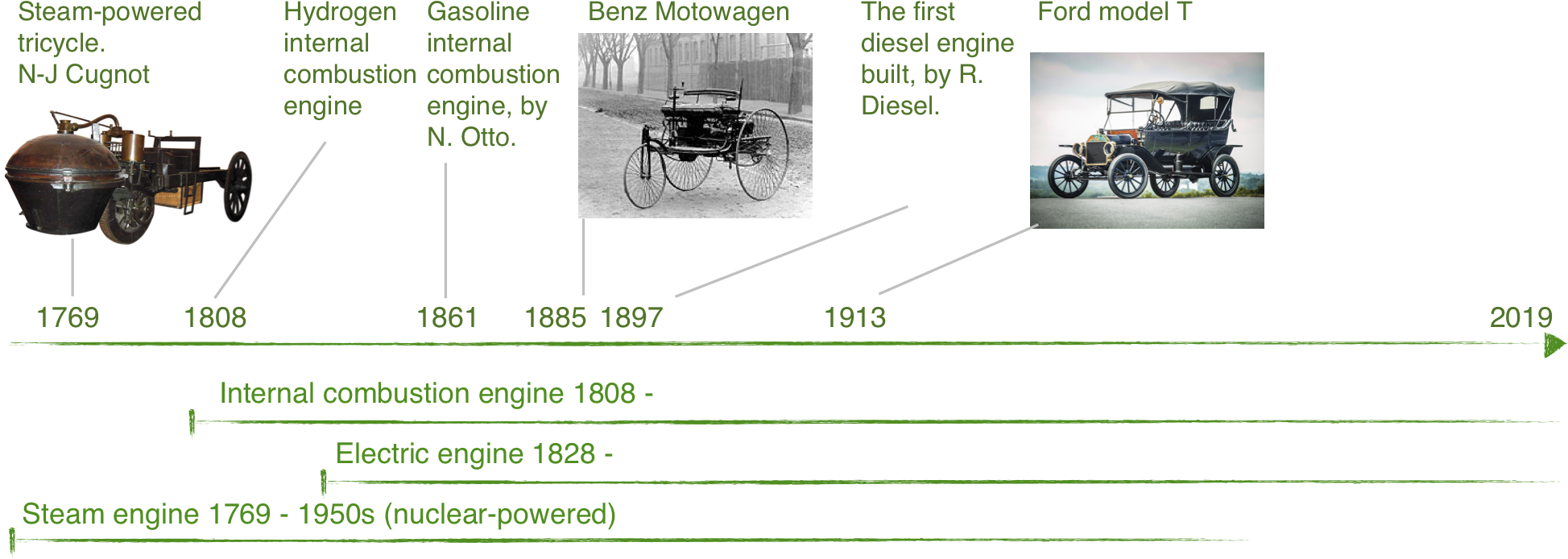

Figure 2 summarises the key events in the development of engines, as well as complete and commercially viable early models of cars.

Frenchmen Cugnot built and drove the first steam-powered tricycle down the streets of Paris in 1769.

The first internal combustion engines emerged in 1808 and was powered by hydrogen.

But neither the steam nor hydrogen engine caught on in large scale.

Almost half a century later, Nikolaus Otto built the first four-stroke gasoline internal combustion engine in 1861.

Benz Motorwagen was built in 1885 and patented in 1886.

This is now regarded as the birth of the modern car, as the “production” contains several identical copies.

In 1897, Rudolf Diesel invented the diesel engine, which, after undergoing many generations of development, still competes with the gasoline engine for fuel efficiency and power.

The Ford Model T entered market in 1913.

It was the first mass produced and widely adopted car model.

One notable aspect of engine development is that many different technologies co-existed and co-evolved for a long period of time.

For example, new steam engines were designed in 1950s that are powered by small nuclear reactors.

On the other hand, electric engines started in 1928, but it wasn’t until the 2000s that they became widely available to the average driver.

What might this mean for Machine Intelligence?

Algorithms are the engines that power Machine Intelligence.

Over the last few decades, many new algorithms are being invented and perfected for performance and speed.

The development of new algorithms will continue by the growing community of Machine Intelligence researchers.

We should expect a constant stream of incremental improvements for the currently most popular algorithm paradigm - such as neural networks, as well as occasional disruptive changes.

We liken the different types of algorithms (such as neural networks or decisions trees) to the different technologies that power a car.

For example, electric cars went from experimental to mass-market in the last decade, and solar car product was only recently shown to public. One may ask if another algorithm may replace neural networks soon?

The coexistence of multiple core technologies also holds for Machine Intelligence algorithms – not every machine learning problem needs a deep neural network – generalised linear models, boosting and ensemble classifiers, kernel machines, and others will continue to play their roles in a variety of scenarios.

What this implies is that students of Machine Intelligence should start from a broad foundation of different mathematical tools and decision-making paradigms, to be able to adapt to the technology shifts in the future.

We also observe that whole-system prototypes and engines are developed simultaneously.

Internet companies have been practicing building large online systems driven by Machine Intelligence algorithms for the past two decades or so.

Each large company has its home-brew machine learning systems and peripheral components.

Cars have evolved for more than a decade (1885 to 1913) from being a niche product (Benz Motowagen) to a mass market (Ford Model T).

The technical community is working hard on common components and reusable systems, one may wonder what the “Model T” equivalent of machine learning looks like?

2. Legislation

Every complex machine can fail, sometimes due to faulty parts, sometimes due to humans who are in or around the car.

The history of car accidents and mishaps is as long as the history of the car itself.

The first fatal accident happened in 1869 when a passenger was thrown out a experimental steam car.

The year 1896 saw the first pedestrian fatality in London when the car was traveling at 4 miles per hour.

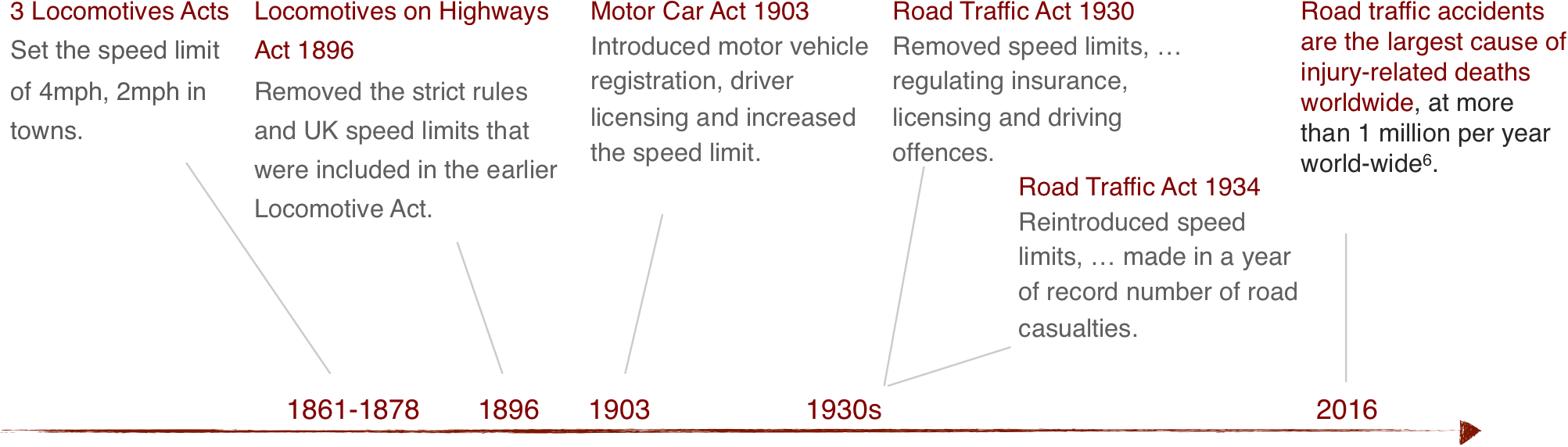

Legislations on the behaviours of cars and humans developed thereafter, with key events summarised in Figure 3.

One notable aspect of the legislations is the speed limit.

The Locomotives on Highways Act 1861 introduced the first speed limit of 10 mph on open roads, or 5mph in inhabited areas.

The second edition The Locomotive Act 1865 reduced this limit to a draconian 4mph (2mph in towns), and required that a man carrying a red flag to walk in front of the vehicle hauling multiple wagons.

This restriction essentially eliminated the advantage of cars over horse-drawn carriages, and was a result of powerful lobbying by those with interests in railways and horse-drawn vehicles.

The Locomotives on Highways Act 1896 relaxed the speed limit to 14 mph, set in comparison to ‘furious driving’ of horse carriages.

This event has been celebrated by motor enthusiasts with the London to Brighton Run to this day.

Eight years later, the Motor Car Act 1903 raised the speed limit to 20 mph, and introduced the crime of reckless driving with associated penalties.

In 1930, the speed limit was controversially removed.

The documented reason was that it was difficult to enforce.

Four years later, in the face of a record number of road casualties (7,343 deaths and 231,603 injuries), Road Traffic Act 1934 reintroduced a 30mph speed limit in built-up areas - a limit similar to those in use today.

Key measures of safety and liability was also developed in the same era, including car registration, classification of motor vehicles, driver licensing, driving test, requirement for insurance, driving offences, and others.

What might this mean for Machine Intelligence? The automotive industry is heavily regulated.

Regulations cover how different components are designed, what safety features are included, and the overall performance of any given vehicle, such as noise and emission levels.

In addition, there are independent agencies who provide vehicles safety ratings and extensive consumer surveys on user ratings.

As recent incidents show, the regulation of Machine Intelligence systems is in its very early stages.

One main part of existing regulation is around data protection and access restrictions.

But they are far from sufficient, for instance, hidden attributes such as race and gender can be inferred even if not explicitly collected.

Just like the emission standards, MI companies should be transparent on what data is collected and how its used.

The public should not be shocked at what our voice assistants at home listens to.

In addition to regulating the components and processes of the machine (cars), we can ponder what the Machine Intelligence counterparts may be for behaviour and competence.

Should practitioners hold a license (or a university-level course in the subject, or a graduate degree), and be subjected to continuous monitoring (such as the learning and re-certification required for medical practitioners)?

Who should be liable for mishaps resulting from the Machine Intelligence system – the practitioner, the company employing them, or the producer of the original algorithm?

There is considerable urgency for Machine Intelligence researchers, practitioners and society at large to understand the safety, moral and ethical implications of MI systems.

There is hope that this will happen more proactively than the Road Traffic Act of 1934.

Let’s do better than merely reacting to a record number of accidents!

3. Peripheral components and eras of evolution

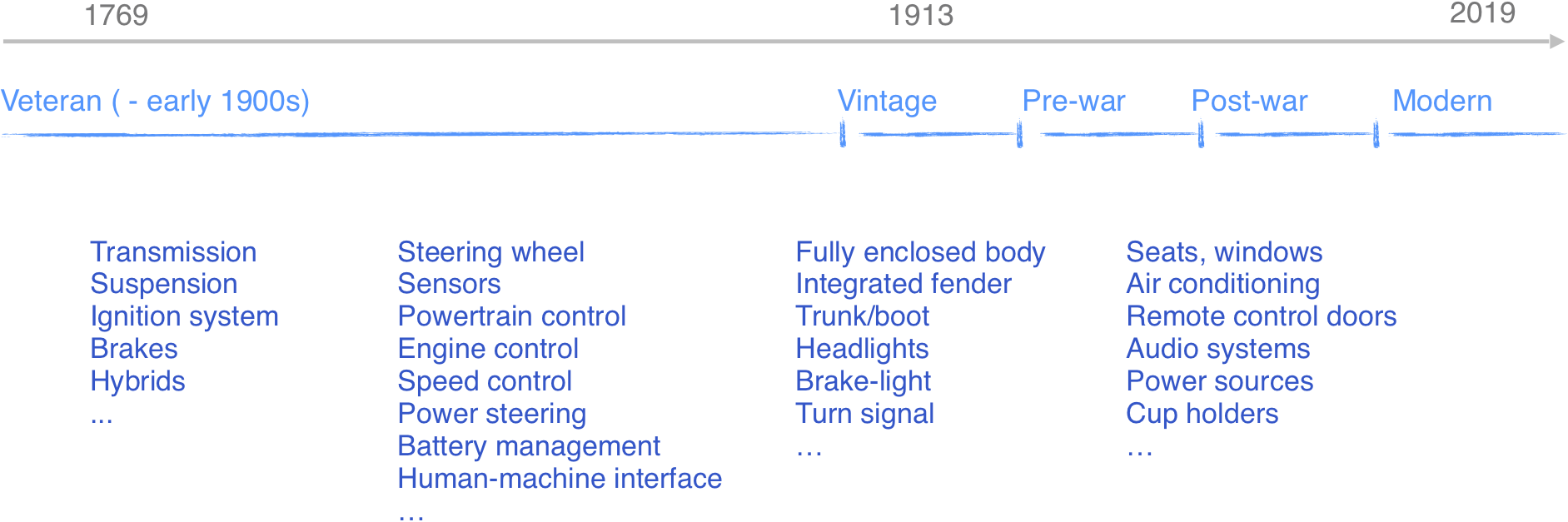

It is estimated that over 100,000 patents created the modern automobile and motorcycle8.

Besides the chassis and powertrain that can be considered as the skeleton and muscular system of the car, many other components make the rest of the machine practical, comfortable and even enjoyable to drive and ride.

Figure 4 lays out a timeline of the five eras of invention, and a non-exhaustive list of common components.

What might this mean for Machine Intelligence? There are direct analogies from some of these parts to those in a Machine Intelligence system.

The notion of a dashboard is now commonplace in deployed machine learning systems9, the importance of which is underscored by well-publicized cases of data drift and prediction failure over time in non-mission critical systems10.

Other analogies may be still open for imagination, such as the counter-part of headlights, Antilock Breaking System (ABS), and others.

On the adoption and use of automobiles, the machine went from being operated by hobbist or requiring specialised knowledge to operate (chauffeurs) to being a skill that a large fraction of the population has.

In the understanding and maintenance of automobiles, on one hand the reliability improved so much that a driver no longer need to be prepared to stop on the road, pop the hood open, and supply crucial liquids (water, oil, fluid).

On the other hand, the contents of popular mechanics and fix-your-own-car videos has proliferated, that people can learn to fix many small problems via self-education.

One may ask, what will it take for machine learning to be both accessible for novices and enthusiasts alike?

Finally, one may ask what Machine Intelligence applications may evolved into, analogous to the diverse styles and functions of automobiles, e.g., 4-wheel drives, convertibles, SUVs, trucks, vans, buses, or even road trains?

Parting thoughts

When one thinks of a car these days, the first reaction usually isn’t that it is complex or dangerous.

This is despite the fact that automobiles brought dramatic changes in how we travel, how we live, how our cities and rural landscape look like in the past century or so.

The recent development on AI and Machine Intelligence may seem scary because much of their effects and implications are unknown.

In the early 20th century, people have approached cars with the same level of apprehension.

The not-so-short history on how humans humanised cars may offer a few fruitful thoughts on how we should humanise Machine Intelligence.

This is a timely subject that needs much intellectual energy from students, the public, policy makers and researchers all alike.

One place for such thinking and debate is the HMI project, stay tuned!

Epilogue: where does the analogy stop?

There are several limitations to the analogy here.

The first is whether cars will (and should) play the current role in our transportation systems.

There are well-argued recent cases against private cars in media outlets11 and film12 for a range of reasons from reducing accidents due to human errors, to saving time and improving urban traffic, to reducing pollution and greenhouse gas.

There are many social, technological and environmental reasons to believe imminent changes await in our use of cars – AI itself is one of them.

A second one is the distinction between designers/builders, drivers, and passengers of cars, and the analogous roles in Machine Intelligence.

AI is at a stage where designers and builders of new technical components make headlines13, and the roles of drivers and passengers are important but not not yet clear.

For example, are users of voice assistants or online recommendation systems drivers or passengers, how much users should understand the role of data sources in delivering the services at hand, and how much the AI engine should explain to the users.

1 This article is based on part of my talk given at the "AI, Politics and Security" workshop jointly held by [ANU Bell School](http://bellschool.anu.edu.au/) and [LeverhulmeCFI](http://lcfi.ac.uk/) in March 2019.

2 We are grateful for the free clipart for cars http://clipart-library.com/cartoon-car-images-free.html

3 All car-related knowledge in this post comes from Wikipedia, a big thank you to Wikipedians for their curation of such knowledge. Any mis-interpretations are mine. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Car, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_automobile

4 There is a long tradition of making the analogy of history and mirror in Chinese official culture (a common phrase being 以史为鉴). For example, the name of a grand history book, Zi Zhi Tong Jian (资治通鉴) refers to mirrors explicitly https://www.theepochtimes.com/grand-book-of-history-a-mirror-for-chinese-emperors_1346839.html.

5 Wikipedia pages on UK Locomotive Acts, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locomotive_Acts, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locomotives_on_Highways_Act_1896, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motor_Car_Act_1903, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Road_Traffic_Act_1930, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Road_Traffic_Act_1934

6 Ning P, Schwebel DC, Huang H, Li L, Li J, Hu G (2016) Global Progress in Road Injury Mortality since 2010. PLoS ONE 11(10): e0164560. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0164560

7 How many parts is each car made of?, Toyota Children’s Question Room, retrieved July 2019 https://www.toyota.co.jp/en/kids/faq/d/01/04/

8 Jerina, Nataša G. (May 2014). “Turin Charter ratified by FIVA”. TICCIH. http://ticcih.org/turin-charter-ratified-by-fiva-federation-internationale-des-vehicules-anciens/, Retrieved July 2019.

9 Google Cloud Machine Learning Engine description, https://cloud.google.com/ml-engine/, Retrieved July 2019.

10 Lazer, D., Kennedy, R., King, G., & Vespignani, A. (2014). The parable of Google Flu: traps in big data analysis. Science, 343(6176), 1203-1205.

11 Nathan Heller, Was the Automotive Era a Terrible Mistake? 22 July 2019 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/07/29/was-the-automotive-era-a-terrible-mistake

12 2040, directed by Damon Gameau, https://www.madmanfilms.com.au/2040film/

13 2018 ACM A.M. Turing Award Laureates, https://awards.acm.org/about/2018-turing